“This is not asthma. He needs to go back.”

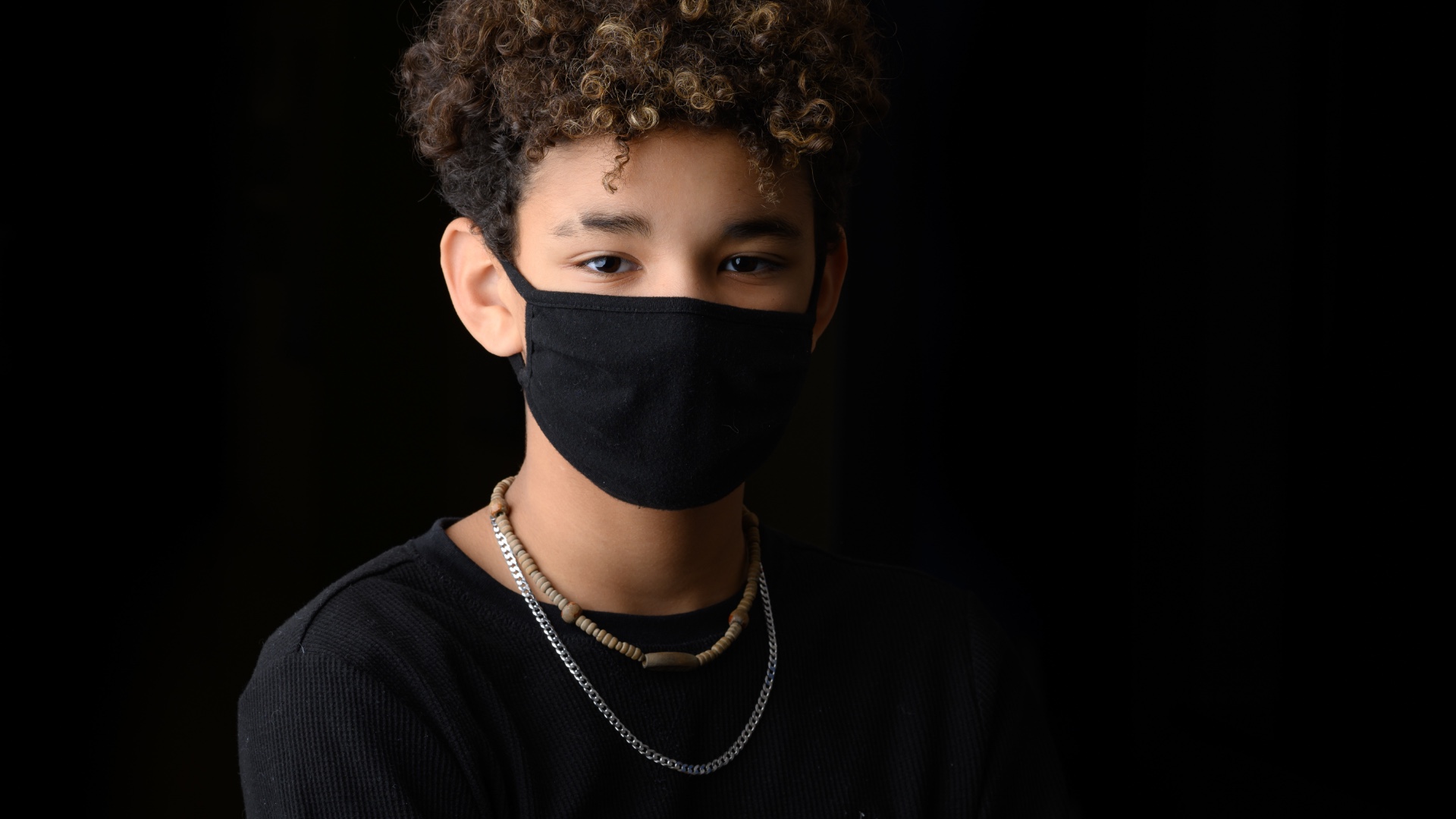

On a Sunday afternoon in April of 2019, 12-year-old AJ Dunn was doing what he does most weekends: playing in the yard with his cousins. “They were just wrestling around and he comes running in the house, holding his chest and saying his head was hurting,” said his mom, Samantha Coleman. His mother tried to get him to calm down and breathe slowly—and eventually he did. But AJ and Samantha started to notice a pattern: any pressure on AJ’s chest would lead to difficulty breathing. “Even when I would get in a hot tub or take a shower, I couldn't face the water, because it would take my breath away,” AJ said.

His mom took him to their local doctor in Springfield, Kentucky, where AJ was diagnosed with asthma and given an inhaler. For the next few weeks, he made sure to take his inhaler everywhere he went, especially to football practice.

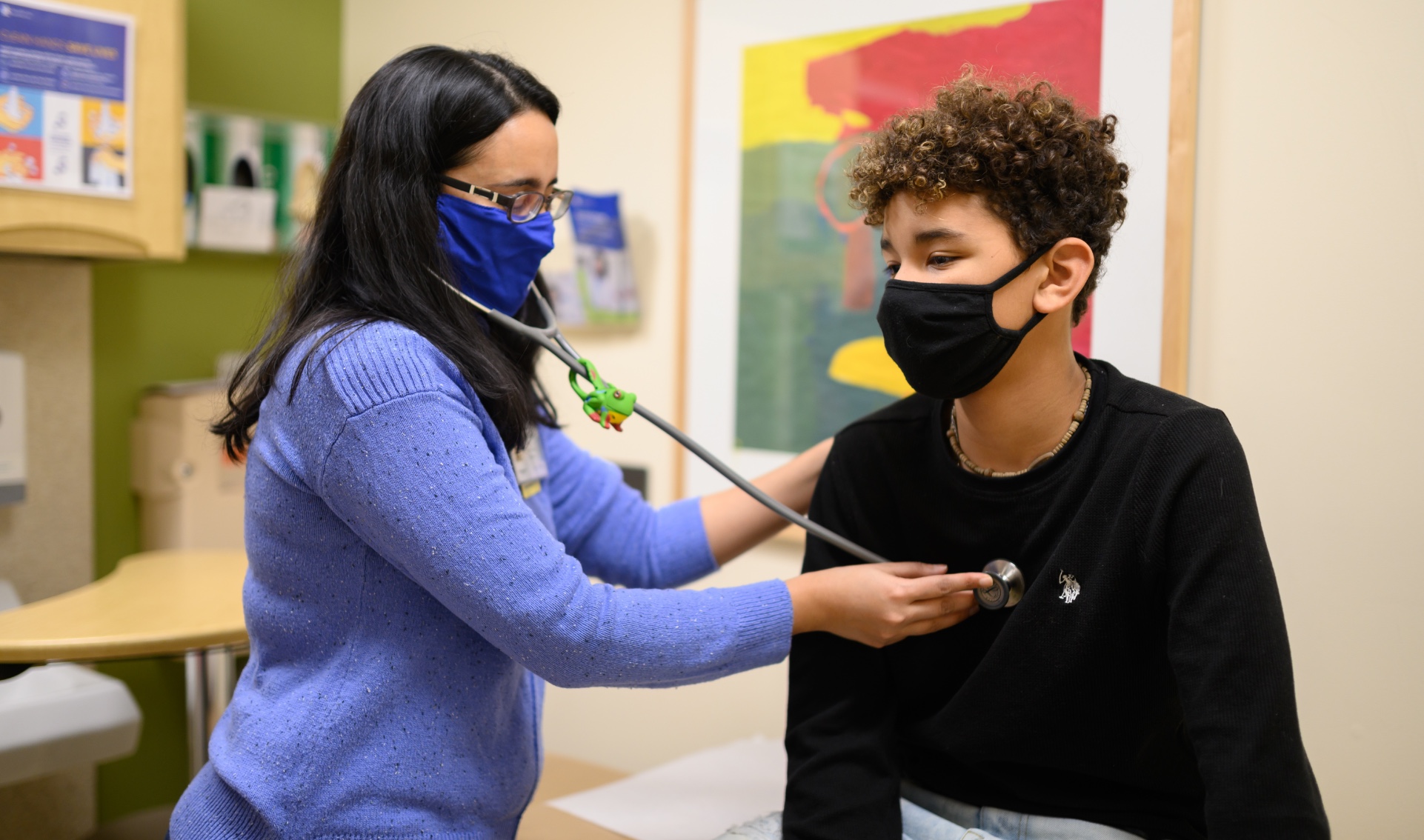

Then, one day during practice, AJ was hit in the chest during a play. His inhaler didn’t help—it made him feel even more lightheaded. “The school nurse called that day and said, ‘This is not asthma. He needs to go back.’ She saved his life, basically,” Samantha remembers. AJ went back to the doctor and was hooked up to an EKG machine to monitor his heart. When his heartbeat came back abnormal, Samantha took AJ to Lexington, where he was placed under the care of Dr. Preeti Ramachandran at the Congenital Heart Clinic at UK HealthCare’s Kentucky Children’s Hospital.

In Dr. Ramachandran’s role as a pediatric cardiologist, she performs CT and MRI scans on children of all ages. The imaging allows her and her team to get a closer look at how a child’s heart is functioning, helping them make the right diagnosis. “I’m a very visual person and like to see the problem in front of me,” said Dr. Ramachandran. “Imaging is a core part of pediatric cardiology practice—it allows us to see a child’s heart, which can vary from simple holes in the heart to conditions where the connections of the heart may be more complex. It’s important to visualize these defects and how they work before planning surgery for the patient.”

Once AJ entered the clinic, Dr. Ramachandran performed another EKG on him—the first test most patients in her care receive. When she wasn’t satisfied with the EKG results, she decided they needed a closer look at AJ’s heart, in the form of an echocardiogram: a type of cardiac imaging that allows doctors to perform an ultrasound of the heart. This imaging technique assesses every single structure of the heart, from valves to chambers to arteries. Lastly, Dr. Ramachandran performed a cardiac CT scan to ensure she could see exactly where the abnormality was occurring. The final scan confirmed Dr. Ramachandran’s hunch: AJ had anomalous coronary arteries, a birth defect that causes a person’s coronary arteries to be shaped abnormally. In AJ’s case, his left coronary artery was coming off the right side of his heart, leading to a lack of oxygenated blood flow. It’s a heart defect that affects less than one percent of the population and presents in different ways, or not at all. It’s also an abnormality that often leads to death.

“We don’t know why kids present symptoms the way they do,” Dr. Ramachandran says. “It depends on each individual’s sensitivity. AJ’s was unbearable chest pains when he played sports. In that regard, he’s very lucky.” Because AJ’s abnormality led to unmissable symptoms, they were able to diagnose him before it was too late. His heart defect could be corrected with open-heart surgery, which was performed in June of 2019. They opened up AJ’s coronary artery and made an incision in the wall of his heart, allowing them to move the artery to the correct location, restoring proper blood flow—and saving his life.

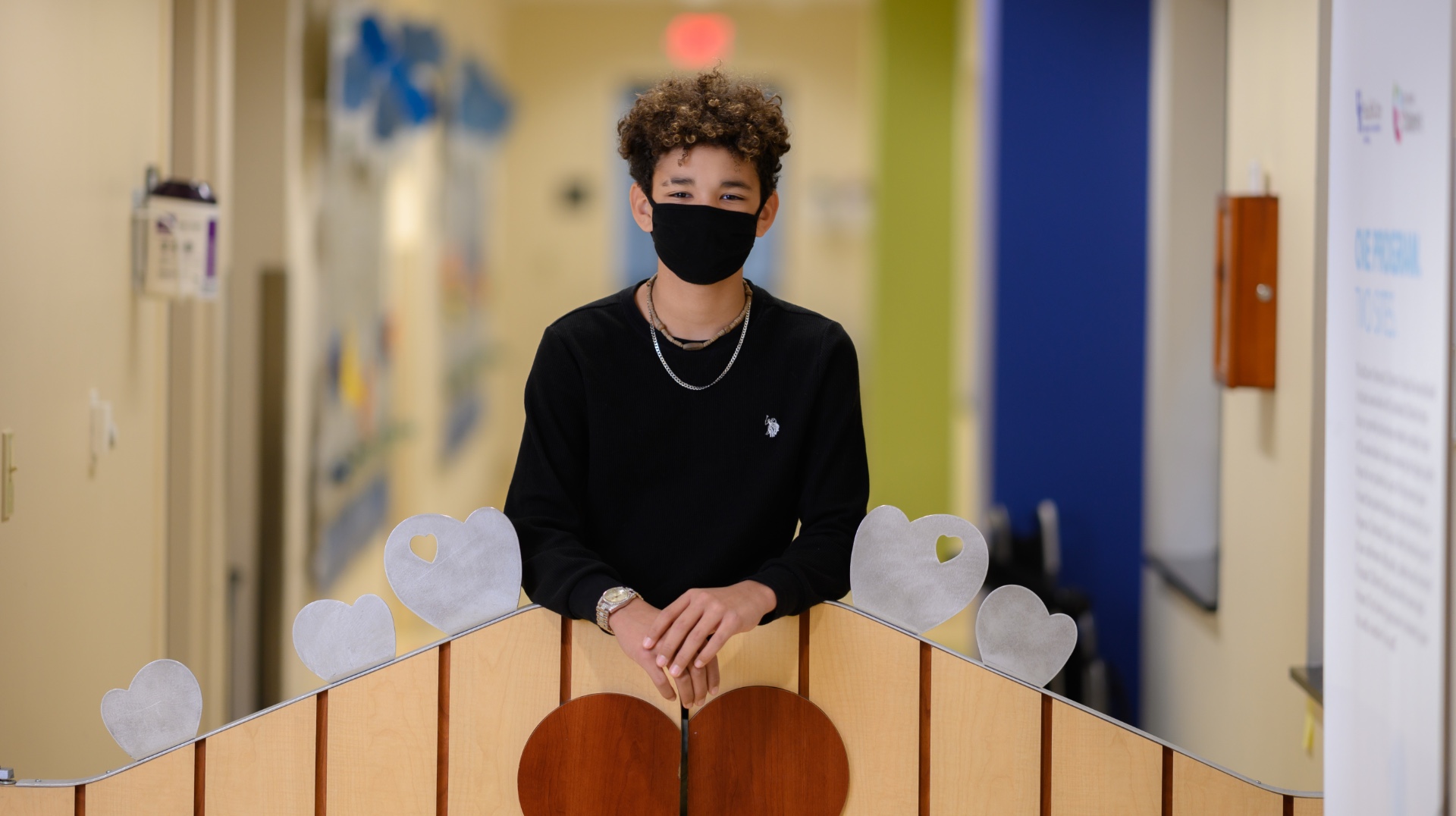

While AJ’s surgery fixed his heart, it also put his football participation on hold. “I was kind of sad there for a little bit, because I always love to play football and I was like, well, I'm never going to be able to play again.” But after a series of follow-up assessments, including a stress test, Dr. Ramachandran and her team cleared AJ to return to the field in October of 2019, for the first time in more than six months. Since then, he’s been able to run and play normally, from being a wide receiver on his football team to playing basketball, hunting, even doing Civil War reenactments. You’d never know he had open-heart surgery.

“They said that if he would've gone on and played sports that year, he could have been one of those kids that just dropped on the field,” said Samantha. “That was scary,” AJ agreed. “But I feel normal now. Half the time, I kind of forget all that happened for me to feel this way, because I’m able to run around like normal people do.”